I submit this column on Tuesdays. On Tuesday February 1, I had just sat at my desk when the shock news that the megaconglomerate Amazon had shut down Westland Books – a major Indian publisher, homegrown in Chennai over six decades and owned by Amazon for the last five years – came without a single warning. My two latest books (one barely a month old, one barely a year old) were released by this publisher. I didn’t write my column that day; a week later, I’m struggling to resume my usual rhythms. This holds true for hundreds of directly affected people. Despair reigns. The knowledge that our books (our babies!) will leave the market, become out of print, and that remaining copies will be physically destroyed has been completely shattering.

Speculation is rife about how this closure happened at all, but what is not widely discussed is just how short a window of time remains for Westland titles to reach the market. The huge backlist will go out of print on February 28, with a deadline of February 15 for bookstores to order their final stock. The small frontlist goes out of print on March 31. March 15 is the presumed final order deadline, but may be sooner as the company and distributors navigate this unprecedented situation.

The size of and titles listed in these final orders depend purely on reader purchases right now. Bookstores will have to pay upfront; their lists will be smaller than most imagine. While books won’t be recalled – that is, if they aren’t returned first (due to e-commerce’s popularity, brick-and-mortar bookshops return stock regularly, which the author then has subtracted from her royalties) – they will be few and rare.

Other than the importance of purchasing books urgently, there are some other things that readers need to know about this situation. For example: the date for last orders will likely also apply to libraries. Readers can convince institutions to bring books in, as well as personally donate Westland titles to community libraries. The Free Libraries Network (https://www.fln.org.in) is a good place to start.

As for republication, the reality is that except in the event of a complete buyout of the entire catalogue, renewed life is simply not possible for every book. Even if a book finds a second publisher, it won’t re-enter the market until the new publisher honours their existing contracts, which could mean a year or two, especially with so many now jostling for room. Self-publishing is expensive and impractical; not all books work digitally either.

The viscerality of pulping has horrified most authors and readers. Many ask: but why? It’s industry practice: unsold books are pulped regularly to clear warehouse space. Since a shuttered company can neither store nor legally sell its books, any that remain unhomed when all efforts are exhausted – including (hopefully) its own library donations – will suffer this fate.

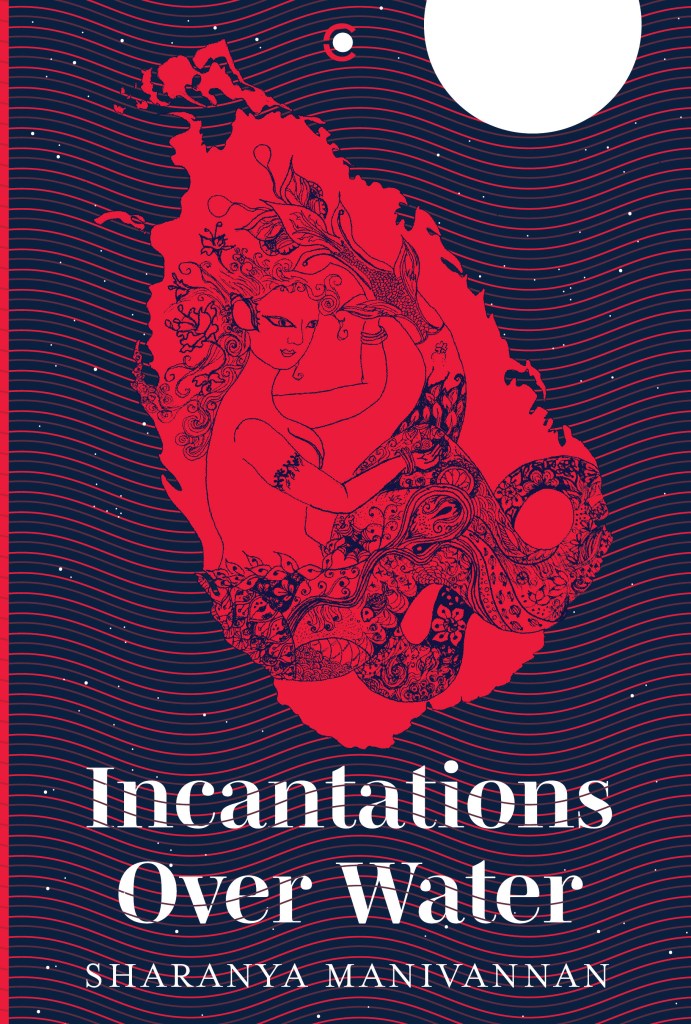

I don’t want to imagine it, but sleeplessly grieving I do. I wonder if they’ll give me the ashes of my Incantations Over Water and Mermaids In The Moonlight, and some day those will be mingled with mine and immersed in the lagoon that we all came from…

An edited version appeared in The New Indian Express in February 2022. “The Venus Flytrap” appears in Chennai’s City Express supplement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.