Sharanya Manivannan writes and illustrates fiction, poetry, children’s literature and non-fiction. She was born in 1985, grew up in Sri Lanka and Malaysia, and has lived in India since 2007.

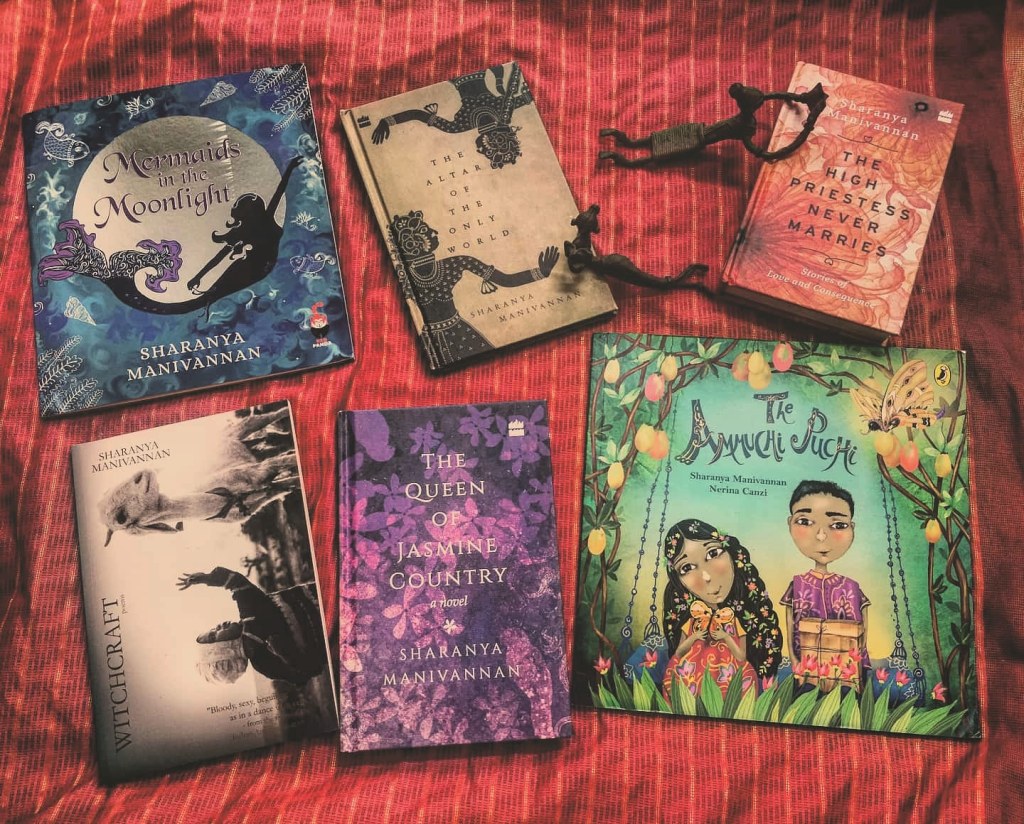

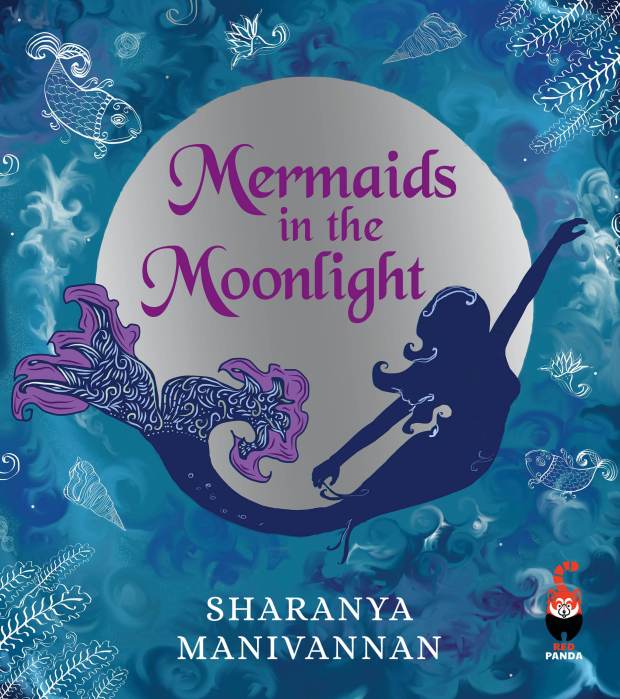

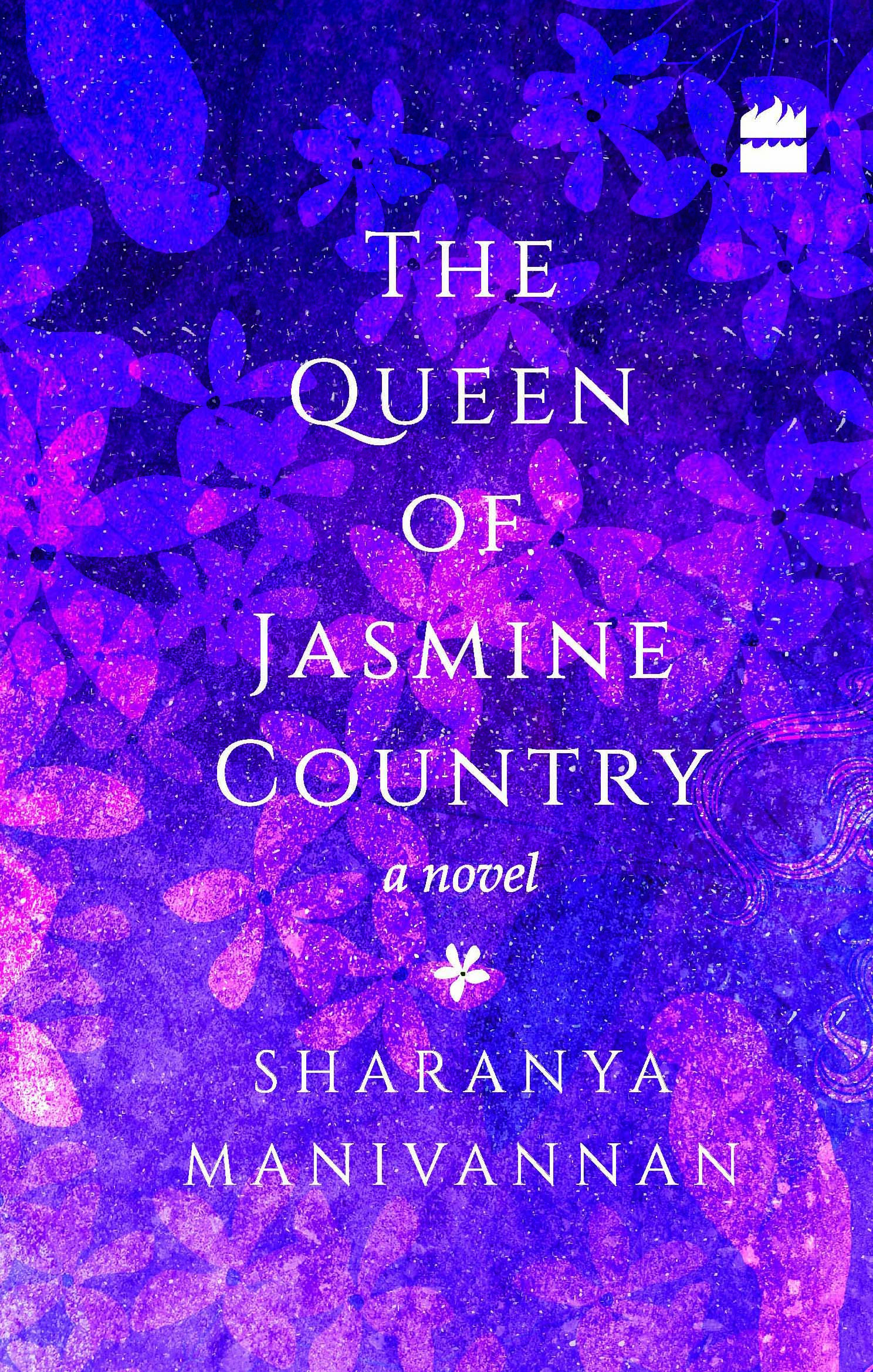

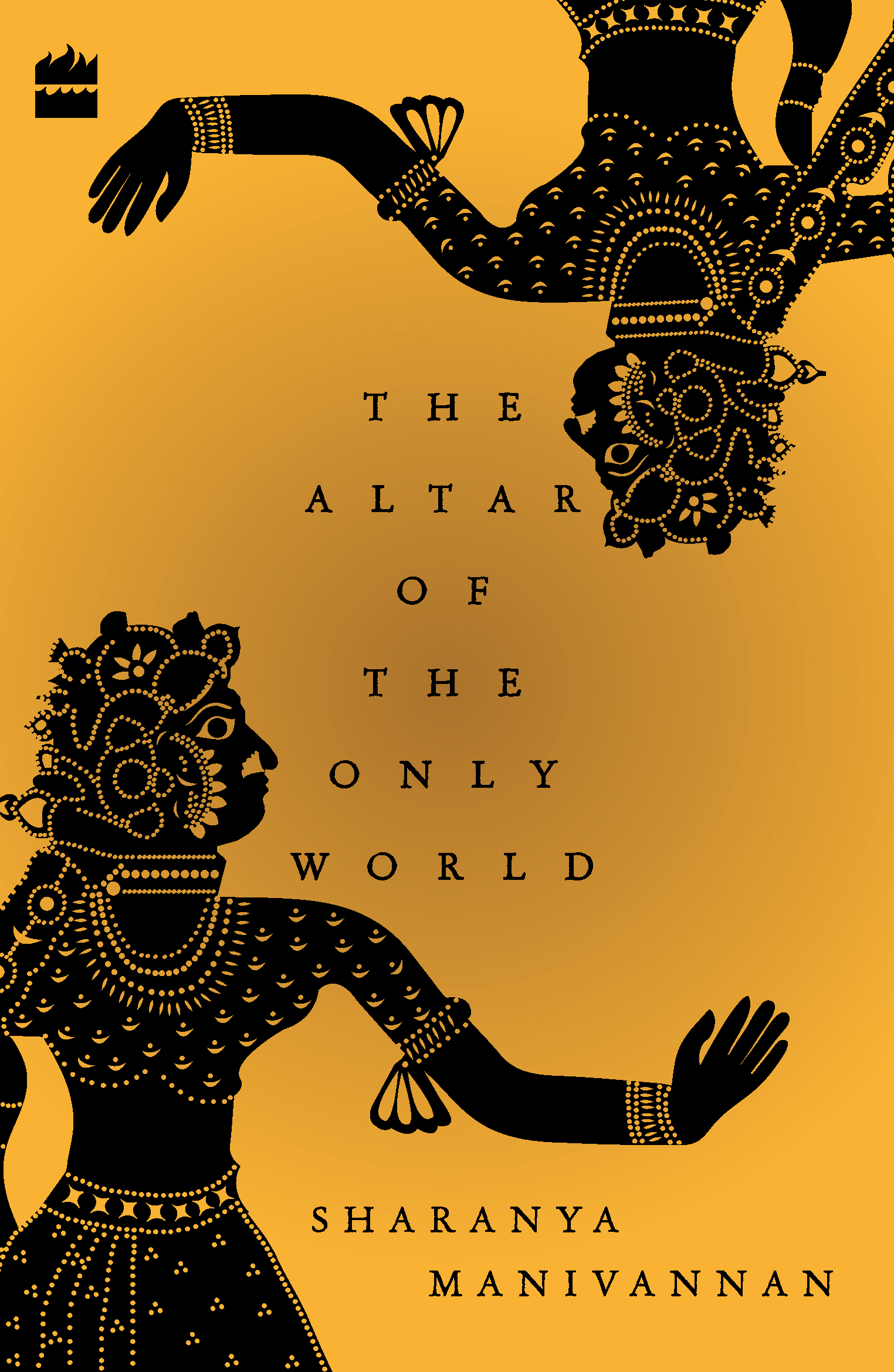

Sharanya’s books are: Incantations Over Water (graphic novel, 2021), Mermaids In The Moonlight (picturebook, 2021), The Queen of Jasmine Country (novel, 2018), The Altar of the Only World (poetry, 2017), The High Priestess Never Marries (short fiction, 2016), The Ammuchi Puchi (picturebook, 2016) and Witchcraft (poetry, 2008).

Her short story collection The High Priestess Never Marries won a 2016 South Asia Laadli Award. Her books have also been nominated for The JCB Prize, The Hindu Prize, The Neev Book Award, The Atta Galatta-Bangalore Literature Festival Book Prize, The Tata Literature Live! First Book Award and other honours.

In 2024, Sharanya received a Devi Award, which recognizes exceptional women for dynamism and innovation across fields. She has also been a recipient of the Lavanya Sankaran Fellowship from Sangam House (2008-2009) and the Kolam Fellowship from Kolam Writers’ Workshop (2023).

Her poetry has appeared in anthologies including Out Of Sri Lanka, Eleven Ways To Love and The Red Hen Anthology of Contemporary Indian Writing. Her fiction has appeared in anthologies including The Female Complaint: Tales Of Unruly Women and Influenced: Stories From The Lockdown. Her essays have appeared in anthologies including Walking Towards Ourselves: Indian Women Tell Their Stories and Knot For Keeps: Writing The Modern Marriage. Her poetry, fiction and non-fiction have also been widely published in magazines internationally. Sharanya’s work has been nominated by magazines thrice for the Pushcart Prize: for “Nine Postcards From The Pondicherry Border” by Flycatcher Magazine in 2012 (fiction), for “I Will Come Bearing Mangoes” by Rougarou Magazine in 2012 (poetry) and for “Echo, Shadow, Ether, Mirrorlight” by Marrow Magazine in 2023 (fiction). She also received a 2012 Elle Fiction Award for “Greed And The Gandhi Quartet” (fiction).

As a journalist, she has received two Laadli Awards For Gender Sensitivity for a piece about books and classical dance in The Caravan. Her personal and current affairs column, “The Venus Flytrap” appears in The New Indian Express (2008-2011 and 2015-present).

She has presented her work in Asia, Europe and Australia. In 2012, she represented Malaysia at Poetry Parnassus, part of the London Cultural Olympiad. In 2015, she was specially commissioned to write and recite a poem at the Commonwealth Day Observance at Westminster Abbey, UK.

Drawing on her own experiences of dislocation, abuse and resilience, Sharanya is known for work that amalgamates deeply personal questions about identity, trauma and longing with a feminist framework that is intended to impact the collective imagination about how to care for ourselves, for nature and for one another.

Sharanya is currently working on fiction and non-fiction manuscripts. She does not have an agent, and can be contacted for professional enquiries at sharanya(dot)manivannan(at)gmail(dot)com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.